CAN Human Rights Exhibition Landscape

Project Title:

The Exhibition Landscape of Human Rights in Canada: An Ethnographic Study into Process and Design

Link to the full dissertation beast: https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/items/21fb54b8-9fec-491d-9f49-2abbe1a1f044

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

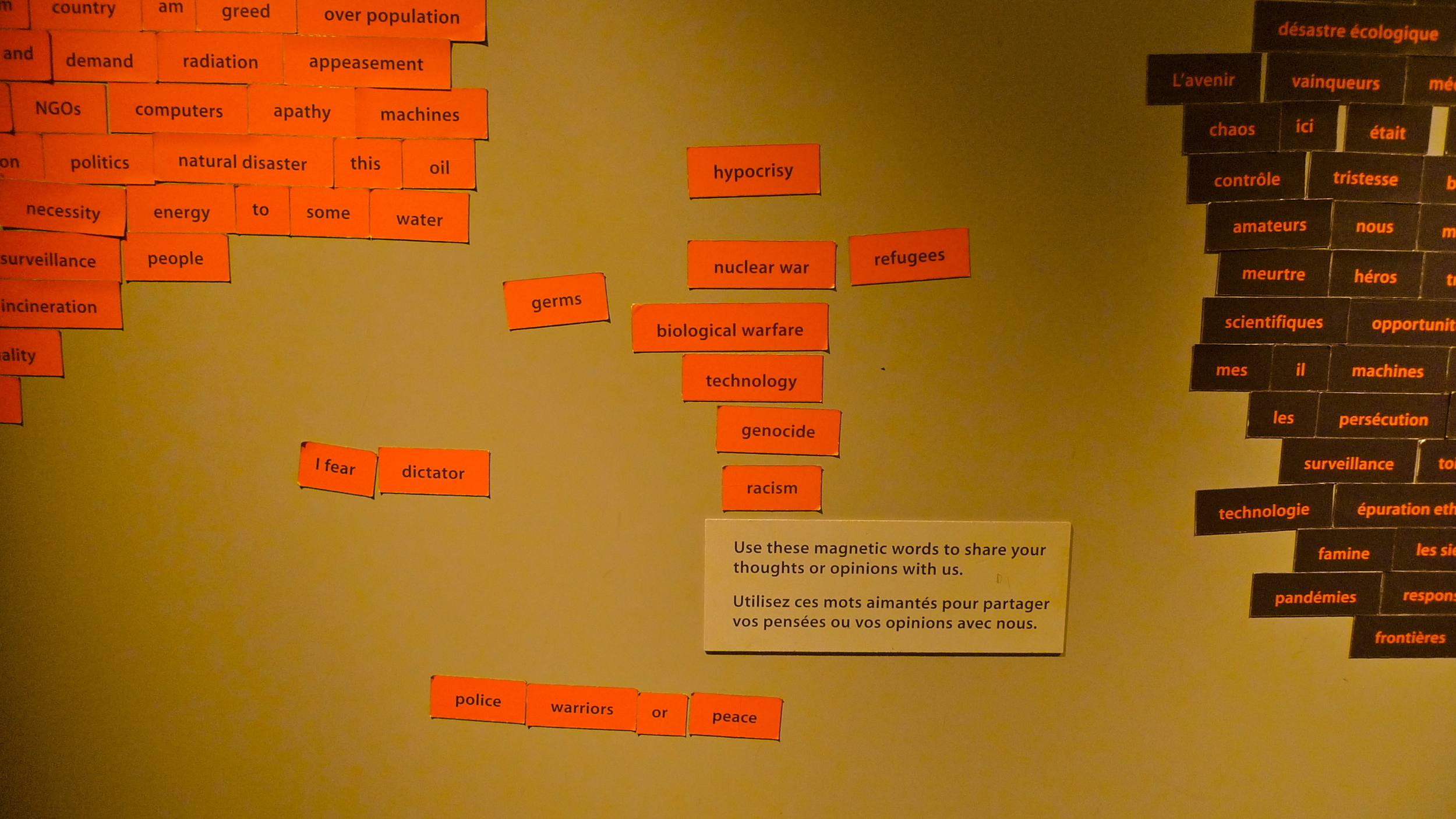

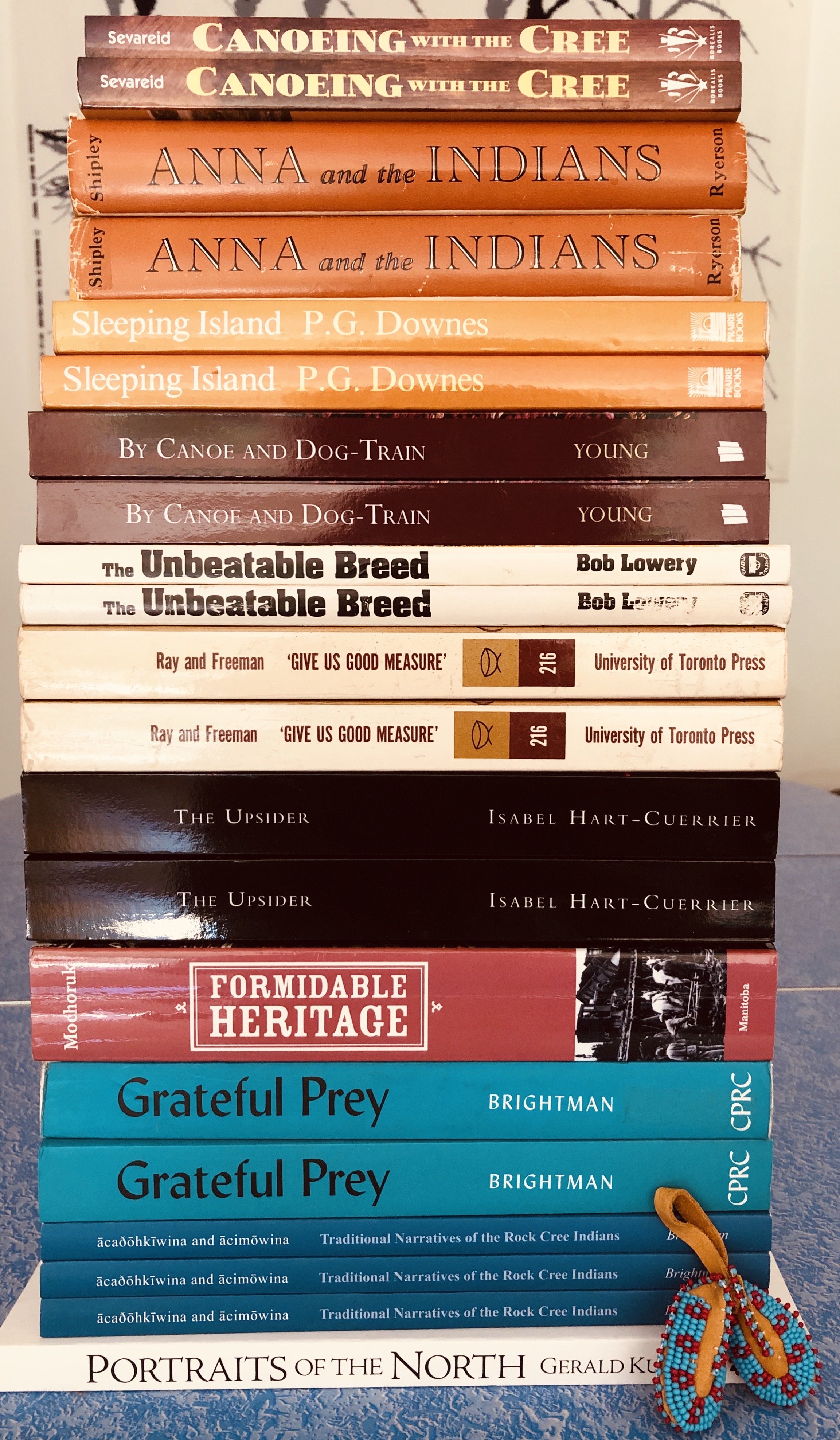

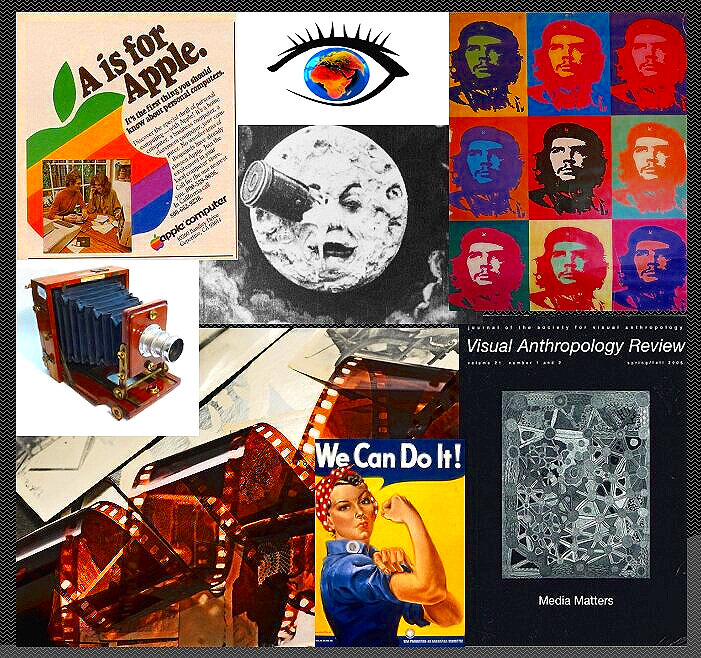

***This page served as a place for me to share my doctoral research as it progressed from 2014-2017. During these years, this online space became a place for me to think through what human rights related museological practice might actually look like in Canada. The use of images throughout my research provided me with a critical way to visually conceptualize how various practices, places, and institutions in Canada are both connected to one another, while also informing one another. The visual landscape produced through the lens of a camera and the sensory practice of reflecting on being in place worked together to produce a narrative of human rights curatorial/programming/educational work happening in Canada museums up until, and during, this time. Under each photograph I have added “snip-its” of information describing this project ranging from my project abstract; forms of methodological and theoretical practice I incorporated in my work; major research findings; and a series of random thoughts delivered as auto-ethnographic reflections that surfaced in my mind as I roamed through the various phases of fieldwork, research analysis, and writing contemplation during the duration of my doctorate. Though I added thoughts and photographs sporadically during my degree, my final written dissertation incorporated a photo-essay chapter that was built from the drafts of this space. The essay shared here now, is an edited version from my final dissertation.

The Official Project Abstract:

As places where multiple cultures, faiths, and artistic practices come together, museums exist as physical sites of intersection. They are at once sites of debate, dialogue, protest, and partnership. This intersection uniquely positions museums as capable of tackling challenging subject matter related to human rights and global justice. Through interviews conducted with heritage professionals from eight different institutions across Canada, this dissertation analyses the curatorial practices, methods of collections research, exhibition design strategies, educational programming, and public outreach initiatives of these institutions as they relate to Canada’s three official national apologies delivered in the House of Commons for: The Japanese Canadian Internment during World War II; the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusions Laws; and Indian Residential Schools. This research considers: (1) how are human rights abuses that have occurred in Canada are presently being defined and displayed in Canadian galleries and exhibition spaces; (2) the nature of collaborations and partnerships involved when designing exhibitions of this nature; and (3) the role of both material culture and survivor testimony in processes of creating human rights exhibitions. As a multi-sited ethnographic study into the process of museological project design, the results of this research provide valuable insights into the challenges faced and the strategies deployed by heritage professionals when working with difficult subject matter. This research finds that emotional experiences factor greatly in processes of project development about challenging subject matter. Working with survivors of trauma is not just about creating a successful exhibition; in the end the exhibition is but one part of the museological process. Museological work of this nature typically involves working directly with survivors of trauma with exhibitions that are driven in development more often by the personal narratives shared by survivors and less so by objects in collections. As such, this strain of museological work comes with the possibility for survivors to heal from past trauma through the sharing of their experiences and this healing is part of the transformative potential of museological work. Additionally, this research strongly indicates that the flexibility of smaller, community-driven institutions where the needs of participants in the project are central to the curation process, stand as strong examples of human rights work produced through the space of the museum. As such partnerships between smaller galleries and larger museums exist as valuable sites of institutional collaboration in Canada. Finally, this research indicates museums are situated as key players in the ongoing development of human rights discourses in Canada. Museums create and contribute to the general public’s legal understandings of rights and justice as produced through the pedagogies of museum practice, and these pedagogies come to educate the public about acts of discrimination, cultural inequality, violence, and genocide that have occurred in Canada. Such contributions position museums as public institutions as valuable to twenty-first century rights-based research in Canada.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The data collected for this project is primarily based on semi structure interviews I conducted with museum curators, lead project researchers, directors, programmers, academics, and community activists and historians about their experiences creating exhibitions that deal or have dealt with difficult subject matter pertaining to Canada's three official national apologies delivered in the House of Commons for: the Japanese Canadian Internment during WWII (1988), the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusions Laws (2006), and the Indian Residential School system (2008). This project has been an effort to identify the processes of museum work involved when designing exhibitions of this nature - what are the strategies and challenges of working with this type of material in an exhibition context? What partnerships are formed in order to build emotionally charged exhibitions? How do heritage professionals view the role of survivor testimony and material culture in processes of creating human rights exhibitions? Are these exhibitions contributing to broader discussions of human rights in Canada? These are some examples of my main research questions that form the backbone for the full series of questions I asked during our conversations

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

With eight fieldwork sites, much of my time for this research was spent in gallery spaces. As a recording device, the camera provided not only a tool to visually capture my experiences, but the images I took provided an analytical space for me to think through my field work experiences in new ways during the process of data analysis. Images can show us things maybe we didn’t fully see in the photographic moment, helping us to both document our roles as documenters and opening new lines of inquiry and reflection. The process of editing, whether photographs, film, or sound clips, is an imaginative and active place where researchers bring media together in new and creative ways of knowledge production (Boudreault-Fournier 2017; Pink 2007). For me, the process of editing became an important place of contemplation during this research. All the images were edited for clarity, some were cropped to highlight aspects of the photo. Others have been creatively altered in Photoshop. It was while choosing images, playing with colours, cropping, adding layers, that my mind wandered into the spaces in between the images. It was in this space of wandering that new insights developed that were not part of my gallery visits or interviews. It was through spending time with my images that a narrative began to emerge out from this research and this narrative enabled me to see how my field sites are connected to each other; connected to the cities they reside in; and connected to various rights issues and heritage spaces across Canada.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

Research is filled with unexpected moments. Something that stood out to me early on in this project was just how significant my eight field sites are within the city they reside. This connection is significant not only when thinking about the work an institution attempts to conduct, but the collection it cares for, the community of people it is attempting to reach, and the physical presence these buildings have on the urban landscape. Museums, art galleries, and historic sites are part of the arts and culture fabric of an urban environment, and together they form a network within a city based on historic and contemporary artistic and cultural practices that connects directly to specific sites of historic memory and to collective understandings of past events (Blumer 2015; Busby et al. 2015; Phillips 2006, 2015). For example, walking through Chinatown in Vancouver and the area around Powell Street in east Vancouver where Canada’s largest group of Japanese Canadians resided prior to WWII, gave me a better appreciation for how particular heritage spaces such as the Chinese Canadian Military Museum and the Nikkei Cultural Centre are intricately connected to this part of the city. In this sense heritage spaces, particularly those to do with rights-related events, form a network—or landscape—across the cities where they reside but also come together to form a larger network across Canada. A network that comes together to tell a larger story about the development of rights in Canada and the role that heritage spaces across the country play in this development. Walking is a sensory, experiential form of critical practice where reflection comes through moments being in place (de Certeau 1984; Ingold 2000; Moretti 2017; Pink 2008, 2009, 2012). And so, like a 19th century Flâneur, walking through the cities where my research sites were located has been a vital part of the field work process, which is a bonus because I love walking and getting lost in cities—both mentally and physically—as a necessary act of meditation for my mind.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The CMHR was my first official fieldwork stop back in September 2014. Though I couldn't actually get any tickets (via the lottery system set in place by the museum for the opening weekend) to go inside the galleries this visit, this turned out to be a strange blessing in disguise. In addition to spending time at the opening ceremonies and public events planned for the opening weekend, I spent a lot of my time in Winnipeg walking around the city, talking with people, and taking in a general sense of what it means for this institution to have been built in this place. The CMHR has very much marked landscape with its presence and it is a presence that is felt. Given the timing of the opening of this museum coinciding with the beginning of my research year, I noticed early on as I moved on to further research sites after the opening of the CMHR, thoughts from the people I interviewed as well as the many exhibitions I reviewed for this project, have all become in many ways, part of a response to the creation of the CMHR. Given Canada now has a museum like this, that is a museum "for human rights", this project has been an opportunity to put the CMHR and the exhibitions built in this institution in conversation with other institutions across the country that also have experience, in some cases several decades worth, with this type of exhibition development. There are many examples of these across Canada and my research really only touches on a fragment of these. The real question I was left with after leaving this first visit (and also my second in Feb 2015) was how and if, the CMHR is conducting or ready to conduct the curatorial work required to work on human rights issues. There is a great difference between human rights displayed thematically and human rights work being done through a cultural institution.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

While visiting Winnipeg, I spent considerable time reflecting on the CMHR's physical presence on the landscape of the city. This museum is one of the only national institutions in Canada to be built outside of the capital city of Ottawa. The choice to build in Winnipeg and in the Forks area of the city was a very deliberate decision. I found myself fascinated with the city of Winnipeg and grateful for the opportunity to become connected to this place via my work. There are so many layers of historical depth to this city and these layers mark the landscape in many ways.

Winnipeg is a culturally diverse city that carries a municipal consciousness of social and political justice. Winnipeg was at one time the physical and commercial center of Canada: Union Station at the edge of the Forks was the center of the Canadian Railway, where commerce, goods, and people gathered. The Forks at one time had immigration sheds where new comers to the Prairies were stationed during the late 1800s and early 1900s before moving to on to other parts of the country. Winnipeg was also the site of Canada's first workers strike in 1919, which funneled into the downtown streets near the Forks. The CMHR today sits across from Saint Boniface, the home to the Métis Government, where the legacy of Louis Riel and the Red River Rebellion exists as a strong reminder that the province of Manitoba was created to protect the rights of the francophone and Métis communities in the newly developed country of Canada after Confederation in 1867 (Busby et al. 2015; Newman and Levine 2014).

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

These many layers of history are in part why the CMHR was very consciously built in this place. The Forks was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1974 by the Government of Canada, it has the official Government sign, numerous public pieces of art, a big market, live music - it has the feel of a tourist attraction with restaurants, a market, open spaces for public performances, and other museum spaces such as the Children's Museum and the Railway Museum.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Winnipeg and The Forks also have a different kind of feeling... the kind where you can feel history seeping in you when you look around. This is the palpable kind of history. The Forks is the place where the Red River and the Assiniboine River meet (pictured here) on what is Treaty One territory. It was a place of connection and trade for Indigenous peoples for thousands of years and later for fur traders seeking to supply the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company. The Forks today with the crossing of the rivers is a place where people celebrate (!) the winter months by skating down the rivers, listening to music, and drinking Caribou (fortified wine). It is also the place where recently a number of bodies have pulled to shore of the river banks, including many Indigenous women, some only young girls. The Forks has a different kind of feeling... the kind where you can feel history seeping in you when you look around. This is the palpable kind of history.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

While the opening of the museum may have fallen a bit flat on many fronts—the limited tickets for one—what the opening did provide was a chance for other places, institutions, galleries to join in welcoming a new cultural institution to the city. The Winnipeg Art Gallery held a human rights themed exhibition, the Forks had an exhibition of information panels discussing human rights (previous photo), and pictured here is a chocolate shop celebrated the opening with CMHR-themed treats. As I spent time in the city, I sensed that despite skepticism, there is also some hope that by having a new big museum, a national museum at that, not only will this help spark tourism to the city, but it will also spark the ability for the CMHR to serve as a critical site for human rights dialogue. People seemed genuinely interested in this potential. This is currently where much of the critical scholarly focus on the institution is being place - more on this to come...

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

This a photo of the Winnipeg group Royal Canoe during their set at the CMHR opening events. Though a number of great acts were scheduled, set times for artists were very short (30 mins), and many shows were cancelled due to heavy rain. Controversy also broke out surrounding the performances after A Tribe Called Red, the scheduled headlining group pulled out of the line-up stating they disagreed with the museum's decision not to call Indian Residential Schools an act of genocide against Indigenous people by the Canadian Government. ATCR is an incredibly successful group of three Indigenous DJs based in Ottawa and their decision was a big political statement. Royal Canoe still chose to play, however, they used their super short set time strategically to acknowledge the massive controversies surrounding museum, their own conflicting feelings about playing, and the fact another body was just pulled from the Red River on the day of their performance. They called out Prime Minister Harper's failure to recognize the astonishing number of missing and murder Indigenous women across Canada and for all of us to use the physical presence of this new museum as a reminder of the human rights issues present in this country. This moment and the controversy surrounding this opening was great reminder to me of the power of artists and the important role they continue to play in every society. During this weekend it was musicians - whether in their decision not to play or to play with the use of specific words - who had the courage to take a very public stand on present day understandings human rights in Canada. Not surprising the sun broke through clouds during Royal Canoe's set.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

The museum’s opening was the focus of other forms of protest as well. This image shows the Shoal Lake protest camp that was set up directly opposite the CMHR. Members from Shoal Lake 40 First Nation came to protest the lack of basic resources in their community, including access to clean, running water. Located near the Manitoba/Ontario border, Shoal Lake has been an isolated community for close to a century, after it was cut from the mainland by the provincial government in order to build an aqueduct to supply water to the city of Winnipeg (Lehrer 2015a). This protest was one of many that occurred on the site of the museum grounds during this opening weekend. During my travels, I spoke with many people about their thoughts on this museum, which in almost every case turned into a discussion about human rights. During one casual Saturday night at a friend's place, a few of us were discussing rights, the museum, access to health care, social services, and adequate housing in Winnipeg. In response to this moment one person noted how lucky we were to be able to sit and have this discussion—to be able to sit back and contemplate what human rights are, or should be, about where they are lacking at the very basic level in parts of our cities across the country. I saw this moment as one of the biggest takeaway messages from the opening of this museum. On some strange level, opening a museum with a $350-million-dollar price tag had people talking about rights; simultaneously, the physical site of the museum served as a place where rights were actively being debated and where protests were taking place (see also Lehrer 2015a). In this sense, despite the controversy surrounding the opening of the museum, the CMHR has served as a catalyst for rights-based discussions. Whether the museum is capable of doing the work of human rights—that is the on the ground real work that is required to help people through the outcome of human rights violations while educating others about these experiences—is yet to be seen.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2015

The next stop on this journey was Ottawa (Fig. 14) for the Canadian War Museum and the Canadian Museum of History (formerly Canadian Museum of Civilization). I have had several research trips to Ottawa during my doctorate. Ottawa seems a somewhat unavoidable place in a project that is, in part, an investigation into the construction and deconstruction of Canadian nationalism and identity. Ottawa is the epicenter of Canadian politics; not necessarily the center of political action in Canada, or the center of politically active people, but the epicenter of the federal government. Ottawa is the home to the Parliament of Canada and its urban landscape is composed of the legacy of material wealth and architecture that came from the growth of Canada as a nation during the late 19th century. Ottawa is also home to Library and Archives Canada; the material memory of government action—or, in some cases, inaction—in Canada. These buildings are examples of spaces that constitute the bigger network of heritage institutions and monuments across Canada that contribute to notions of nation building. Within this network these institutions speak to one another, they influence one another, and together they in part, form the physical and visual landscape of heritage memory, contested or otherwise, in Canada.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2015

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

It was interesting to me that throughout a fieldwork year dedicated to gathering evidence of how human rights issues have been and continue to be exhibited in Canada - that in almost every city that I visited for this project I ran into some form of an abortion/anti-abortion protest. There was a constant anti-abortion presence at the opening of the CMHR in Winnipeg for example, though it seemed the protest was rather lost amongst the media spot light that was instead devoted to much larger current issues such as those related to the CMHR exhibition content (the use of the word genocide with reference to Indian Residential Schools for example and the museum's decision NOT to use this word), and the protests related to missing and murdered Indigenous women occurring in Winnipeg and elsewhere across Canada very publicly at this time (both in fall 2014 when this photo was taken and now in 2015 as I write this). This photo here was taken at Parliament Hill in Ottawa. The blue and pink flags are meant to represent boy and girl unborn babies and were place there rather painstakingly by young school kids I would guess to be around 14 or so who attend a nearby Catholic school. I am all for silent protest and this one I will admit was incredibly eye catching - as the sun was setting the flags literally glistened in the sun light. Disturbing to me, however, was the use of children in a protest like this when the likely hood that one or more of the several young girls involved will fall pregnant at a young age given the basic Canadian statistics of pregnancy (or just the basic fact of life-type statistics - as in young pregnancy occurs in EVERY school and always has). Everyone once and a while I am still in shock that a woman's right to her body is STILL so heavily negotiated. I have so much more to say on this but will end it at that.

Image Copyright JC Robinson

The Response, Canada's National War Memorial, is located in Ottawa and dedicated to fallen soldiers of World War I and II and the Korean War. My fieldwork for this project began in fall 2014, which coincided with the 100th anniversary of World War I. Many museums and gallery spaces were exhibiting materials related to this anniversary. This provided an unexpectedly rich layer of exhibition material related to human-rights issues present in war and conflict. I am thankful for how this material has pushed me to consider the role of the world wars in the development of Canada as a nation, particularly considering the role of Indigenous Canadians, Chinese Canadians, and Japanese Canadians in Canada's efforts during WWI and II, despite not being recognized as full Canadian citizens. This photograph gained additional significance for me because shortly after I left Ottawa in the fall of 2014, a terrorist attack happened in this location; Cpl. Nathan Cirillo was shot to death while guarding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, visible in the image. As I write this several years on, I am left to reflect on the everyday violence that is currently occurring in the world. My heart is heavy daily when I hear the latest list of hate-filled cruelty acted out across the world in the name of faith, culture, and fear. I am reminded time and again by world and local events of the continued need for spaces like museums to discuss and debate these events, as well as of the power of art and education to help heal the many heads and hearts of hurt and hate that exist in Canada and elsewhere. I remain optimistic in the potential for all of us to be better human beings. A choice of optimism, in times like these, seems the only logical way to be.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2015

Located in Gatineau, the Canadian Museum of History is about a twenty minute walk across the Royal Alexandra Interprovincial Bridge from Ottawa. The bridge was constructed between 1898-1900 by the Canadian Pacific Railway and today exists as a major traffic route between two provinces.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

The CMH has had many lives.

The founding collection of the museum dates to 1856 as part of the Geological Survey of Canada funded by what was then the Province of Canada. While this strain of collecting began with geological, specifically mineral specimens, surveyors also began collecting objects from Indigenous communities and the Geological Survey of Canada held its first exhibition of Indigenous material in 1862-1863. By the late 19th century, the Geological Survey Museum was open to the public and responsible for collecting flora, fauns, and material related to human history in addition to mineral collections. To aid with this the Royal Society of Canada was established in 1882 to collect ethnological objects and by 1910 an anthropological department is created in the Geological Survey Society. The collection officially becomes the National Museum of Canada from 1910 to 1968, opening in the Victoria Memorial Museum Building in 1911 in Ottawa (now Canada's National Natural History Museum). In 1968 the museum became the Museum of Man and then transitioned again to become the Canadian Museum of Civilization when the museum moved into its current home across the Ottawa River from Parliament Hill in 1989 in the iconic building designed by Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal (Canadian Museum of History 2016). In 2013 the Harper Conservative Government re-branded the museum as the Canadian Museum of History, a move met with much skepticism, not only for the costs associated with such a process at a time when the federal government has pulled or cut funding to many aspects of arts and culture, but towards the political motivations behind such a move that seeks to create a version of Canadian history or Canadian identity through the space of a museum that matches a political agenda (see Aronczyk and Brady 2015; Minsky 2014)

The CMH provides quite a well documented history of the institution where these points were taken from: http://www.historymuseum.ca/about/#tabs

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

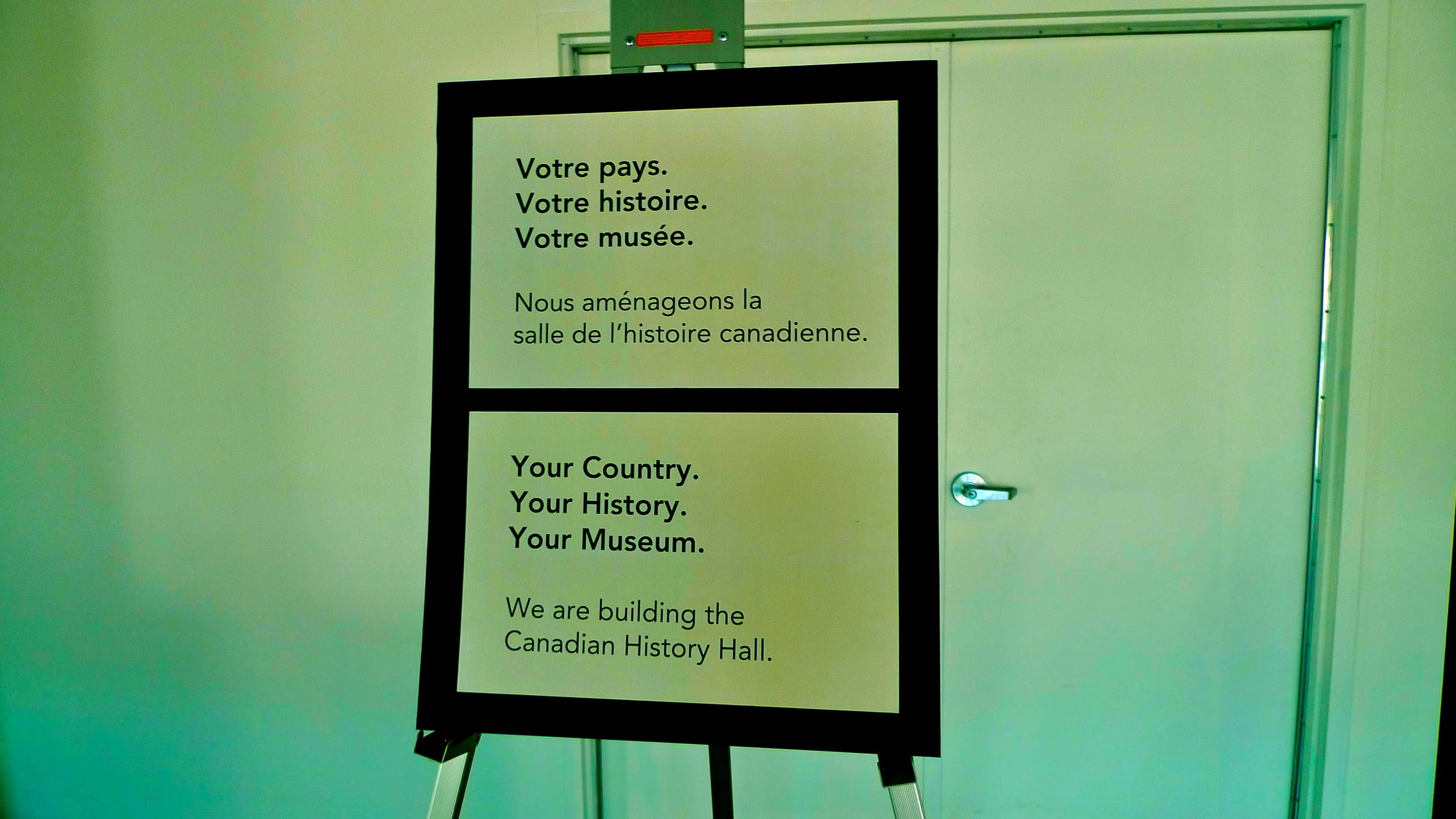

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

During my visit to the CMH in September 2014 (and my subsequent visit during the following June 2015) the Canada History Hall, one of the museum's major galleries and top attractions, was closed for renovations. This is a BIG undertaking by a national museum, not just because of the cost, or the thematic scope—curating an exhibition that covers the entire country from Confederation in 1867 to 2017 (the official opening date) seems like a daunting task—but also in the politics of inclusion and exclusion that come with an exhibition of this nature. Your Country, Your History, Your Museum - so whose history/histories get included? What stories are told and by whom? And in the case of my project, how are the difficult moments in Canada's past portrayed in a national museum exhibition and what partnerships are being created with community organizations in order to do so? Being able to speak with members of the research and curatorial staff early on in the developmental phase of this exhibition provided me with a valuable insight into just how difficult these tasks are for staff but also revealed just how much harder it is to tackle particular subject matter in a national gallery. There is simply not the time or the space and this sense of lacking is one of the major limitations of any national gallery. Like the idea of nationalism itself, not everyone has a place, or feels they are welcome, or feels their story is told accurately. It does not mean that certain staff aren't trying—in fact, an everyday challenge when working in galleries of this side, is this knowing, is having this awareness of this sense of lacking, and in facing the reality that these limitations are in a sense, unavoidable.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

The history of Indian Residential Schools (IRS) has appeared as a subject in many museums across Canada for quite some time, though most often as part of a larger exhibition theme devoted to a general history of Indigenous histories in Canada or settlement history of Canada. Based upon my exhibition viewing, historical photographs that depict IRS have come to dominate the presentation of this material. One such photograph, seen here, is that of a young Cree man named Thomas Moore. Images of his physical transformation from attending the Regina Indian Industrial School in the late 19th century has been widely used in museums and academic publications to illustrate the very visual effect of IRS on the Indigenous body. The picture presents a striking contrast. However, while the placement of such information is essential in positioning the experiences of Indigenous peoples in Canada, small exhibit panels are not necessarily the same as a full exhibition devoted to the experiences of IRS as told through the stories of those who have lived through IRS in their families and communities.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

Like many museums built or renovated during the 1990s, the old Canada History Hall at the CMH made use of large dioramas and reproduction models of moments of Canada’s past. The gallery moves visitors through a timeline that tells of the creation of Canada from the first arrivals of Europeans moving across Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and ending in the North. The message delivered through the exhibition was of a unified version of Canadian Confederation where any sense of conflict is glossed over in the celebration of a united and multicultural country. Gordon-Walker (2016) rightly highlights how government-sponsored acts of displacement, discrimination, and assimilation were presented as acts that occurred in the past and were situated in the exhibition to demonstrate how far Canada had progressed as nation to become a state characterized by equality. Though the museum has been criticized for how the gallery lacked any critical depth in the exhibition and for the use of too many models and reenactments (Dean and Rider 2005), my participants shared with me how many of the staff and visitors frequently expressed how much they have enjoyed this space. The old Canada Hall was by all accounts, a popular tourist attraction. As such my participants shared the difficulty they have had in dismantling an exhibition that has been a successful part of the museum experience for the last 20 years.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

The CMH will open the new Canada History Hall on July 1st as part of Ottawa’s larger Canada 150th celebrations (Fig. 24). Thus, the timing of the completion of this dissertation coincides with the opening of the new gallery. At the time of my interviews, staff at the CMH were very careful not to disclose what themes, stories, or historical moments would be in the gallery and what would not be returning to the gallery from the previous exhibition. The three apologies that have guided this research were part of the old gallery and will all be present in the new Canada Hall after having been re-researched and re-crafted to present these apologies in new ways in the content of Canada in the 20th century. I was told that several consultations had taken place with various cultural community partners to develop content for the gallery, including for the apologies. From my own conversations with David Morrison, the head of Research for the new gallery, conversations began with Andrea Walsh and the Residential and Indian Day School Art Research Program (RIDSAR) at the University of Victoria about how Survivor stories from this group could help tell the stories of residential schools in the Canada Hall. A major finding of my research points to the importance of these institutional partnerships between smaller projects or museums such as RIDSAR and large, national museums with regards to working with difficult histories.

More can be read about the RIDSAR project, including the trip a number of us took to Ottawa to work with the CMH as well as my own involvement with this project: http://www.ajacketfullofstories.com/#/ridsar/

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2015

While in Ottawa I also visited the Canadian War Museum. The current CWM opened in 2005 in Ottawa in the area known as LeBreton Flats. The CWM is part of the Crown Corporation made possible through Canada's Museum Act that also includes the CMH, the Canadian Postal Museum, the Canadian Children's Museum, and the Virtual Museum of New France. Like the CMH, the CWM draws its roots from the late 19th century and the start of a collection based on military items, some 3 million in number. I was not fully aware of just how much the CWM and the CMH share as institutions in terms of resources until I undertook this research project. Many of the interpretive planning, design, and curatorial teams from the CWM, including their former Director, have come on board to help create the new Canada History Hall. Since its opening, the CWM is considered one of Canada's most successful museums with a steady number of visitors every year. The building itself has also garnered much praise architecturally. The architect for the CWM, Raymond Moriyama, was interned along with his Japanese Canadian family during WWII and he acknowledges these experiences in his own process of design development (see In Search of Soul 2005).

A documentary was made on Moriyama's design dream and the building of the CWM:

https://www.knowledge.ca/program/search-soul-building-canadian-war-museum

Image Copyright JC Robinson

There are many reasons that I chose the CWM as a field site. However, the main overarching reason is the theme of the museum itself—war. Museum staff here constantly deal with difficult or troubling material as part of their museological practices. Every exhibition or research project is in some way related to war, and while there are many positive stories about war efforts, home front experiences, victories, and peace projects—there are more stories of violence, hate, destruction, and death. I was curious if and how staff here processed this aspect of their work. Many members of the curatorial staff at the CWM are military historians. For some this provides a distance from the period they specialize in given time that has passed. For others, this means that there is still a community of veterans, the family, or descendants of vets, or those who have experienced conflict first hand who form part of the community that heritage professionals are responsible to consult

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

In addition to temporary gallery spaces, the CWM has four main permanent galleries: Early Wars in Canada; The South African and First World Wars; World War II, The Second World War; and From Cold War to the Present. These galleries focus on the Canadian experience at war, both overseas and on the home front. The galleries use objects, large-scale multimedia, sound, artwork, personal narratives to take visitors through various war efforts in which Canadians have taken part. Veterans occasionally work as tour guides within certain exhibitions giving first-hand accounts of their experiences. The picture here (Fig. 27) is from the WWI gallery and is a mock version of a trench. There are several re-enactment spaces in the CWM and as I was walking through this particular one I was struck by how eerie these spaces can be. There was a strange moment where I was caught somewhere between my own historical reflection of this time and just how distant I am from this reality. This was made especially clear during one of my visits when I entered this space behind a young woman who was taking selfie photographs in the trench. This moment was somewhat of a stark reminder of how museums are somewhat of an in-between space. For me it was space that verged on the real; reminded me of how fortunate I am and yet how distant from the realities of war I live my life. For others, it is so hard to even speculate. For those who have lived a life knowing only peace in homelands, perhaps the distance is part of what we are meant to feel. To be reminded of our freedom.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Given the difficulty of the material the staff of the CWM deal with, it is perhaps not surprising that there were a few exhibitions in my interviews that stood out as being particularly challenging in terms of content and provided a learning experience in terms of strategies that were developed to work with in the future. The two previous photos are examples of this. War and Medicine had exceptionally graphic content in terms of visual imagery throughout the exhibition. Large photographs containing medical procedures developed during times of war were placed on the walls along with early medical tools and technological advancements. The gruesome nature of the content was a point of reflection for the staff, with many noting the difficulty of absorbing such visually disturbing images.

The second exhibition had an even more profound impact on those I interviewed: Deadly Medicine. This was an exhibition about the eugenics movement and was identified as being one of the most difficult projects any of those I interviewed had worked on, given the sheer brutality of what this movement stood for. It was clear from my interviews that exhibitions like these stand as influential sites for the development of new methodological practices, for the very nature of the content requires staff to build training procedures to manage how both staff and visitors engage with the material.

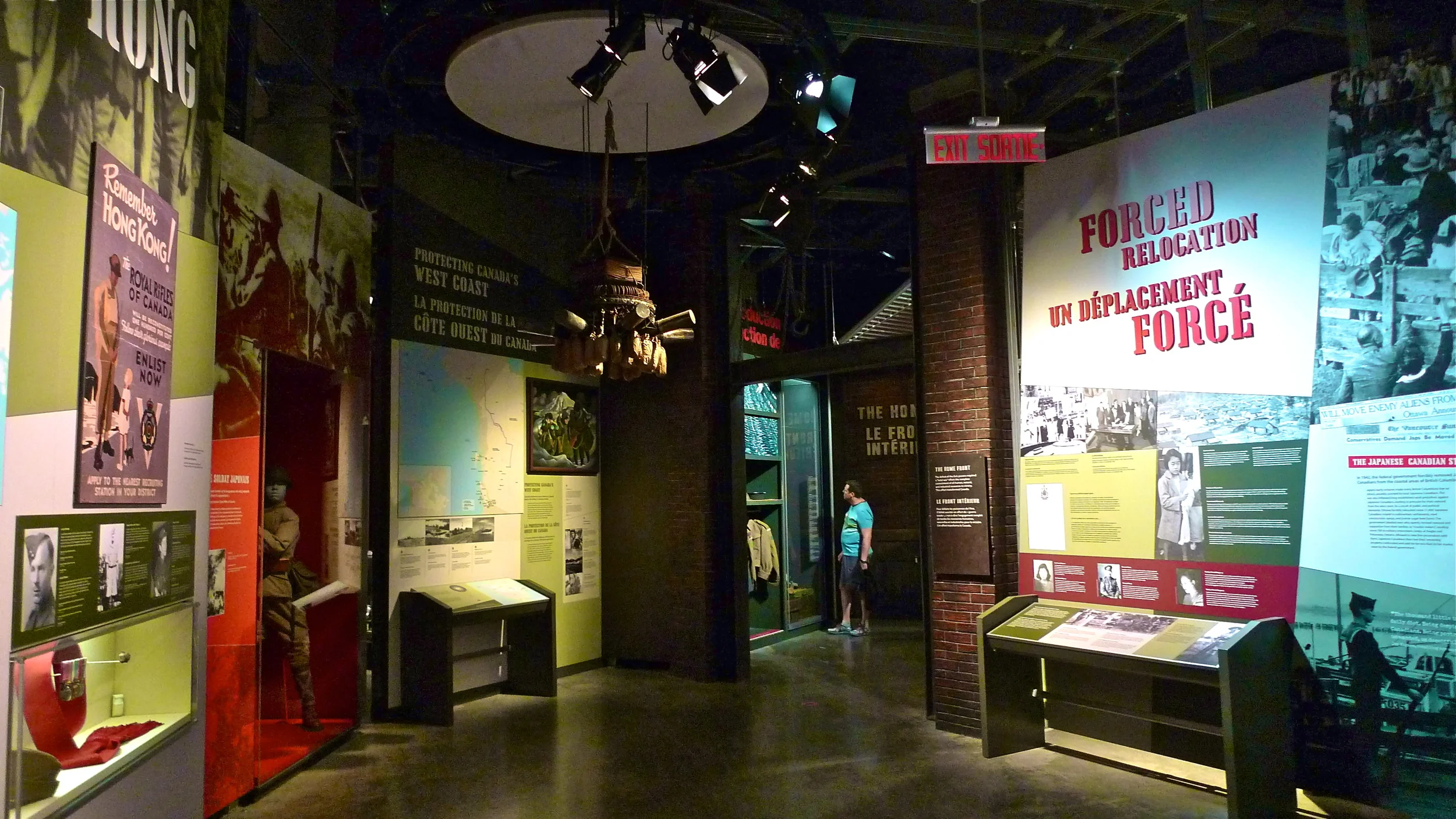

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2014

Part of my interest in the CWM also had to do with how the story of the Japanese Canadian Internment during WWII fit into the larger story of Canada and Canadians at war. Though far from a prominent feature in terms of exhibition capacity within the WWII gallery space, the initial design of the section of the gallery devoted to this topic proved to be an example of how small-yet-powerful physical design decisions have very real impacts on the message being delivered in a gallery. When the gallery initially opened, several members of the larger Japanese Canadian community protested how the Japanese Canadian Internment was positioned within the larger exhibition space. All the permanent galleries in the CWM have long weaving corridors that take visitors chronologically through the start of the conflict featured in the gallery through to the end. In the case of the WWII gallery, the small exhibition space devoted to the Internment is placed directly across from a mannequin model of a fierce Hong Kong solider and an exhibition display about the danger to North America of the invasion of the Pacific and the ruthlessness of war tactics from peoples from this area was. The experience of the layout of this part of the gallery would become the site of protest by many Japanese Canadians.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The Japanese Internment exhibition then leads directly into the entrance of the "At Home" gallery space (seen towards end of this image). When the gallery initially opened, there was a Japanese flag projected across the floor, which physically had to be crossed by gallery visitors to proceed through this portion of the gallery into the “At Home” exhibition space. For protestors of the exhibition, this experience of walking through the space and seeing the discussion of the Internment, labeled as "Forced Relocation" rather than "Internment,” was unsettling. The exhibition panels contained no discussion of the fact that there were many Japanese Canadians who fought for Canada against Japan. This omission of this fact and the placement of the story of Japanese Canadians near the Hong Kong solider set a tone, as I was told, that excused the Internment of Japanese Canadians by the Canadian government. The protests from the community resulted in the exhibition being altered slightly. The flag was removed, proving the power of community voice and importance of community consultation during the design phase of an exhibition. This example also illustrates the power that national galleries have in creating messages about Canadian nationalism through the very structure of their exhibitions.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2015

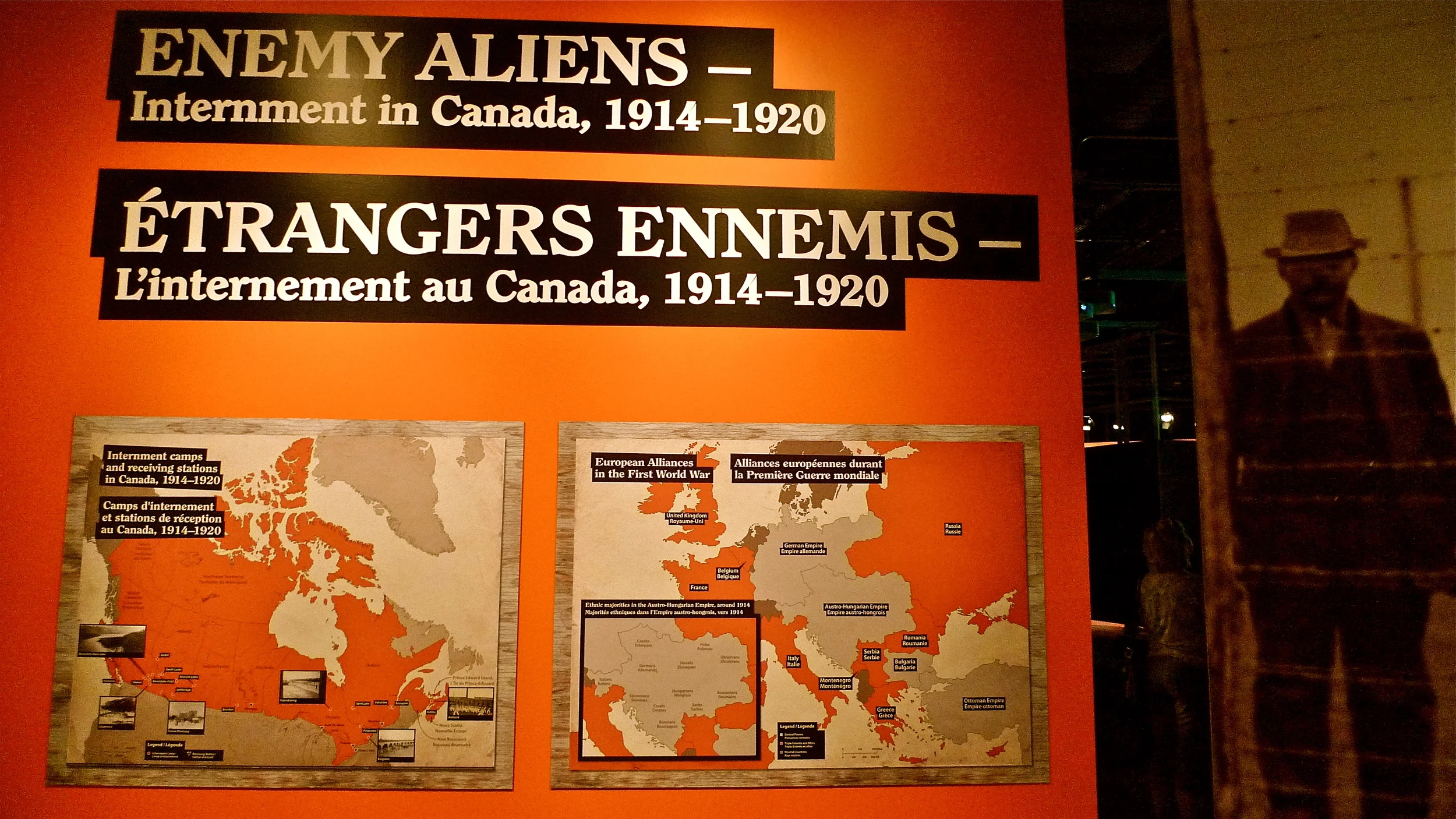

Coincidences are strange things. In addition to my research phase starting alongside the opening of the Canadian Human Rights Museum, my project also coincided with the summer that marked the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I in July 1914. Many of the museums I visited during this first portion of my field work displayed exhibitions related to this marking of time. This included not only the institutions that I officially had in my project for analysis, but also many exhibition spaces in the cities I was visiting. With this historical presence surrounding my journeys, in some cases very vividly through visually striking and at times gruesome exhibitions, the marking of this anniversary came to influence my thinking about challenging subject matter in profound ways. Through the visual medium of photography and later film, early 20th century war and conflict is brought closer to the present, even if many of the survivors are no longer present to share their experiences first hand. Archival visual material from this period has a way of drawing the viewer in and marking the imagination in profound ways. It was the advancements in visual technologies that brought World War I "home" to Canadians for the first time like no other large-scale conflict. With this anniversary came the chance for galleries to revisit, or take on for the first time, new aspects of WWI. For example, the CWM had small exhibition called Enemy Aliens: Internment in Canada 1914-1920, referring to the over 8,000 people, primarily of Ukrainian decent, who were forcibly interned in various camps across Canada through the War Measures Act in Canada. The WWI Internment period in Canada has also resulted in federal apologies to present day descendants of Italian and Ukrainian immigrant communities in Canada (CWM n.d.).

The CWM also provides information on this period of time via their webpage: http://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/enemy-aliens/the-internment-of-ukrainian-canadians/

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The Memorial Hall at the CWM is home to a small narrow space with a single window (Fig. 34) where light shines at an angle on Remembrance Day, November 11th. In a beautiful feat of engineering, the rays illuminate the sole object in the room: the headstone of the tomb of the unknown soldier. Several people I spoke with mentioned the importance of having a physical space where visitors can sit and mentally and emotionally absorb what they have experienced in the galleries. In some circumstances this may be space with the affordance of a couch, bench, or series of chairs. Other examples include specific design features such as an outside garden. These spaces recognize the ability for visiting museums or gallery spaces to fully impact our whole senses. Processing challenging material can, and should be, physical and emotionally exhausting. It should require a moment to step back and process how this experience affects us, and if it does, why? I take a closer look at the responses to these spaces by my participants in Chapter 3 in the context of how to decompress after viewing exhibitions with challenging subject matter.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2016

The Museum of Anthropology (MOA) at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver was my next field site. This institution is special on a personal level as I completed my undergraduate at UBC in 2009 in Anthropology and History, with a specialization in museum studies. I also worked at MOA for three years as a student, and later an intern in the Education and Public Programming Department. With friends, mentors, and now research participants at MOA, conducting interviews here gave me more of an appreciation for collecting data at a field site that is also, in many ways, my own community. The interviews I conducted here were more intimate than those at other institutions. I know that, given my friendships and previous work relationships, my research participants shared a great a deal with me, and our conversations carried a certain depth given my knowledge of the workings of the institution. As a university museum, the origins of MOA's collection dates to the early part of the 20th century when many objects collected from the across the Pacific Islands were donated to UBC by collector and explorer Frank Burnett. However, the museum itself grew out of the work of Harry and Audrey Hawthorn, who came to UBC's Anthropology department in the 1950s to begin documenting the lives of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia on behalf of the Department of Indian Affairs (Hawthorn 1993; Levell 2009). Many of the connections fostered in the 1950s between MOA staff and families or communities across BC remain today, and these long-standing relationships are at the core of MOA's history.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

One example of longstanding working relationships is MOA's relationship with the Musqueam First Nation. Since the 1980s, MOA has followed guidelines negotiated with Musqueam and MOA regarding the proper ways to store, handle, and design exhibitions using their material heritage (Phillips 2000, 2011). This relationship was formalized under the Directorship of Ruth Phillips (1997-2003) with the signing of a Protocol, which Phillips declares, “rebalanced” the power dynamics in the institution (Phillips 2000: 177). By establishing this Protocol MOA recognizes not only Musqueam’s traditional unceded ownership over the territories where UBC and MOA reside, but also this Protocol acknowledges that Musqueam territory spans a large portion of the area of what is now today Vancouver (Phillips 2000). January of 2010 marked the celebration of MOA’s grand re-opening after an extensive renovation project titled "A Partnership of Peoples" made possible in large part (though other major donors also contributed) by a successful application to the Canadian federal government funding program for non-profit organizations called the Canada Foundation for Innovation in 2000 (Phillips 2011). Several major changes came from this renewal project. Highlights of the project include: the Centre for Cultural Research, complete with a library, archive and laboratories for oral history documentation and archaeological analysis; a new temporary exhibition gallery; the reconstruction of MOA’s international permanent galleries formally known as Visible Storage into the Multiversity Galleries; the creation of an online collections database that can also be access through computer systems set up in the new visible storage space; and the beginning of the Reciprocal Research Network. This collaboratively constructed database links the collections of over 14 museums with Indigenous community members, cultural centres, academics, and other museum and art professionals to create digital, collaborative work spaces on collections of objects, particularly Indigenous objects from across North America.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The renewal of the museum also gave staff the opportunity to redesign the front entrance way to more explicitly acknowledge the Musqueam peoples, whose traditional and unceded territories MOA and UBC stand on today. A Musqueam welcome (previous image), and a newly commissioned artwork by Musqueam artist Susan Point (next image) are just two of images which show the Musqueam presence at the Museum’s entrance.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

This photograph is taken inside MOA's Multiversity Galleries, the name given to the redesigned visible storage space where 10,000 objects from MOA's collection are visible. The history of this case began when curator Carol Mayer received a phone call from a potential donor who was the wife of one of the distant relatives of John Williams, an English Reverend murdered on the shores of Erromango, a provincial island of Vanuatu, in 1839. The donor was looking to give objects that were collected by Williams during various missionary expeditions throughout the Pacific (Mayer 2009). It would have been possible in this circumstance to simply accept the donation; however, Mayer chose to approach the situation and the history of these objects differently. This began an extensive dialogue between Mayer, the Williams family, and Ralph Regenvanu, the Director of the Vanuatu Cultural Council, about the possibility of trying to reconcile the history of this collection. There are several examples of "sorry ceremonies" occurring in various parts of the Pacific, which take place between contemporary communities to reconcile with past atrocities that occurred during the colonial period (Mayer, 2009: 7). After much discussion, all parties involved agreed to take part in a sorry ceremony to be held on the 170th-anniversary of the death of John Williams (Mayer, 2009). Mayer traveled with 17 members of the Williams family to Vanuatu to witness an emotional re-enactment of the death of Williams that resulted in new positive memories, the joining of families, and most importantly mutual forgiveness for the actions of the past. Reconciliation is at once a term, process, and series of actions. The work presented in this case is but one small example of many forms of reconciliation currently underway with regards to colonial history at MOA. It highlights the potential for museum work to help with these processes.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2013

In Canadian museological history, MOA has garnered a lot of attention for developing progressive museum practices in Canada, particularly with respect to building better relationships with Indigenous peoples and implementing the guidelines of the Task Force into practice early after its development. However, two exhibitions stood out to me in terms of why I choose to include MOA in this project. The first was the 2011 exhibition The Forgotten that was cancelled prior to installation. This exhibition was composed of Vancouver artist Pamela Masik's very large and gruesome paintings of women, primarily Indigenous women, that had gone missing or been murdered from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside community. From early in planning stages, the exhibition fell under heavy protest by several community groups, primarily from the DTES, because the paintings were seen to be re-traumatizing to the women and families of the women who have disappeared. Though the fallout of this exhibition both was covered by the media and academic scholarship (see Moss 2012; Pinto 2013b), these reviews failed to account for any sense of what MOA had learned as an institution from this experience. I highlight further in my dissertation, how in the wake of the exhibition being cancelled, MOA had to take a step back to reconnect with various community members from the DTES who, along with MOA staff and UBC faculty members, shared a series of group discussions concerning what the issue of missing and murdered women in Canada, but also how MOA could have approached this work differently.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2013

The second exhibition Speaking to Memory, Images, and Voices from St. Michael's Indian Residential School opened at MOA Sept. 18, 2013 to coincide with a visit by Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission to Vancouver. The exhibition was based on a series of photographs recently donated to the MOA archives that were taken by a young girl who attended St. Michael's Indian Residential School in Alert Bay, BC during the 1940s. Curator Bill McLennan sat with many former students from this school with the collection of photos and recorded, if they were interested, Survivors’ memories from their time at the school. The narratives from these interviews are part of the exhibition, with excerpts from these forming quotes on the wall and the full text in binders that were displayed on a long table in the exhibition space. Excerpts from earlier interviews with Survivors that were conducted by the U'Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay in the 1990s were also used. The photographs in the exhibition were mounted with a translucent cover so that names could be written on the photos by visitors to the exhibition who knew and recognized themselves or children in the images in an act of reclaiming their unknown presence from the archive through this act of public remembering. The daughter of the photographer worked with her mother to name as many of the children in the photographs prior to exhibiting them.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2013

As a researcher, I am drawn to the study of material and visual culture. As a branch of anthropological investigation, research conducted under this umbrella has provided valuable ways for thinking about the connection between the material and immaterial world and the value that "things" can have in our lives (Miller 1998). I was curious throughout this project to assess the role of objects used in exhibitions that have direct histories to acts of violence and discrimination and to hear my participants’ reflections on objects that were chosen to be used. The industrial mixer, from the St. Michael’s school is perhaps one of the most powerful that I encountered during this study. As I take up more fully in my dissertation, its inclusion in the exhibition illustrates the potential for objects in exhibition spaces to evoke feelings of empathy, confusion, anger, and sadness in visitors. The baking mixer’s massive size and its presence is striking in a gallery context. The mixer was operated with no protection by many young children who were forced to work at St. Michael's, as was the case at all Indian Residential Schools. Many Survivors interviewed by curator Bill McLennan reflected on the danger of the mixer; how it constantly gave out electric shocks and harmed the young girls who worked in the kitchen. The physical presence of an object such as this provides an additional layer of depth while walking through the exhibition to the experiences encounter by Indigenous people while at these schools. Placed in a small hallway within the exhibition, the space created an overwhelmingly visceral place for contemplation and reflection; once inside it became impossible not to visualize this object in use.

Image Copyright JC Robinson 2013

The exhibition also included large photographs taken of inside St. Michael's by McLennan after the building was no longer in use. The photographs are windows into the empty hallways and staircases that are blanketed in the green-yellowish hue of years passed. The materiality of these photographs draping the walls added such an eeriness to the exhibition space. They provide, like the mixer, a layer of material and visual depth to the exhibition that takes the visitor into the space of St. Michael's in a visceral or emotive way. Quotes from Survivors or policy laid forth in the Indian Act were added to several of the photographs to juxtapose the words with images of the school itself. The exhibition moved up to Alert Bay and was held at the U’Mista Cultural Center in 2014. Many of the large photographs were mounted on to the walls of these school itself. Here again, the photographs created a powerful haunting presence of the hallow hallways and staircases inside of the building as they were plastered on the brick walls of the school before it was demolished in February 2015

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2013

In the exhibition, there was also a large table where visitors could spend time looking through photo albums and reading the full text of Survivors’ stories. They could also take the time to write a comment or reflection to leave in the comment box or in a public comment books. There was also a large black board where visitor thoughts could be written down even more publicly. Education Curator Jill Baird took photos of the board, comment books and the private responses every few days. Though many of the responses acknowledged the exhibition as being a good site of education for information about residential schools, many were also negative and discriminatory, pointing to a need as discussed through my dissertation, for spaces such as museums to house exhibitions of the nature to continue build awareness of these histories.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

My next stop in Vancouver was the Chinese Canadian Military Museum (CCMM). The CCMM is the smallest museum I spent time visiting. It is located on the top floor of the Chinese Canadian Cultural Centre in Chinatown in the east side of Vancouver. The Museum is run entirely by a rotating group of volunteers from the Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society, founded in 1998 with funds provided in large part by private contributions from the Chinese Canadian community in Vancouver. It is a unique museum in that it specializes in Chinese Canadian contributions to the Canadian war effort, particularly to World War I and II. Given this curatorial focus, the museum works with Chinese Canadian War veterans and their families to ensure their histories are recorded and material items from this time collected (CCMM 2016).

See further Chinese Canadian Military Museum http://www.ccmms.ca/about-us/

Additionally a number of great online resources have been created to study Chinese Canadian history through digital archives:

UBC's The Chinese Experience in British Columbia 1850-1950 http://www.library.ubc.ca/chineseinbc/index.html

Chinese Artifacts Project https://ccap.uvic.ca/index.php/

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The CCMM was one of the institutions that made me think about the physical existence of cultural institutions within the city. This area of the city has held a fascination for me since first moving to Vancouver in 2005, and I have spent a lot of time walking the streets of the Downtown Eastside community where Vancouver's Chinatown is located. The east side of Vancouver, located in the traditional territories of the Coast Salish peoples, is historically where many immigrant communities settled in the 19th century, including early Chinese and Japanese settlers. Today Chinatown carries the presence of the early Chinese immigrants who came to Canada to find a better life for themselves and for their families. For some, this was during the gold rush of the 19th century; for others, this was for employment building the Canadian Pacific Railway. After completion of the railway, a head tax was placed on Chinese immigrants in 1885, which remained in place until 1924. From 1923-1947 the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Exclusion Laws, was put in place, restricting immigration to Chinese possessing certain skills. These laws effectively made it impossible for families to remain together and many Chinese men who came to Canada remained separated from their wives and children until after 1947 (Li 2008, Mar 2008; Yu 2001).

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

While walking the streets of Vancouver's Chinatown, I was conscious of the connections between culturally designated spaces in many cities across Canada, a point I take up further in my dissertation. Chinatowns across Canada grew out of policies of discrimination and segregation; in the late 19th and early 20th centuries Chinese were not welcome to live in many parts of Canadian cities and their employment and educational pursuits were restricted (Li 2008; Yee 2005). The walls of Chinatown, as one of my participants explained to me, created a place that was safe and welcoming while providing a barrier from the discriminations inflicted from the surrounding European settler communities. Discrimination that, in many cases throughout Canadian history, erupted in violence, such as the 1907 riots in Vancouver's Chinatown, where many businesses, including this building, were damaged.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The CCMM and the Cultural Centre are framed around the beautiful Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Classical Garden. The Garden, modeled after the classical garden tradition popular during the Ming Dynasty in China, was built during the mid 1980s through the efforts of the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Garden Society. The creation of the Garden was an effort to build connections between Chinese and Euro-American cultures, while also serving as a part of the Chinese Canadian community in Vancouver. Like the cultural centre and the museum, the Garden is a physical marker of Chinese Canadian presence in this part of the city (Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Garden Society of Vancouver 2015).

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The exhibition space at the CCMM is quite small. The hallway seen here forms part of the semi-permanent exhibition area. A small room towards the end of the hall is serves as temporary exhibition space. Beside the hallway is an art gallery run by the Cultural Centre which forms a large part of the second floor and that also serves as an event space. In this sense, the CCMM collection and exhibitions are embedded into the larger context of Chinese Canadian culture within the building, and the exhibitions are encountered by the community on a frequent basis given their location in such an active community space. The semi-permanent gallery area, which has altered since the taking of this photo, is a place for the material collection to be shown. Given the small funding available to the museum, displays are quite simple in design. Here cases of medals achieved by certain veterans are shown alongside the biography and photograph of the veteran.

*This part of the exhibition area has been modified since 2014 when this photo was taken as a new curator has come on board post my interviews.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The CCMM has a small temporary exhibition space with exhibitions that rotate roughly every year. Though the exhibition space is small, it functions as a physical place to juxtapose the experiences that Chinese Canadian vets had while at war with the experiences they encountered once they returned in Canada. When Chinese Canadians served in WWI and WWII they did so without being considered Canadian citizens. It was not until 1947 that Chinese Canadians could receive citizenship and Exclusion Acts were lifted, allowing families that had been separated through these laws to be reunited. The timeline of these events can be traced through the computer portal that is a permanent fixture in the gallery. During my visits the gallery was featuring an exhibition on Chinese Canadians who fought in WWI given the anniversary of the start of the War was in the fall of 2014.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

This large photographic reproduction of the image of three women receiving their citizenship strongly illustrates much of the intent of this museum and the focus of many of the exhibitions. When veterans returned to Canada after WWII and fought for enfranchisement, it was the Chinese Canadian war effort during the early 20th century that laid the foundation for those of Chinese ancestry to be accepted as citizens of Canada. The fight for equality is the message in this exhibition space. The stories of veterans are celebrated alongside the rights of Chinese Canadians. In early 2017, the CCMM organized a walk through the east side of Vancouver that included several veterans and Indigenous community members to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Canadian Charter for Rights and Freedoms (see Ryan 2017). Though the museum itself is small, how the war effort was directly connected to the fight for equality in Canada is a message that is strongly delivered in the exhibitions, programming, and events that the museum takes part in.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

With the museum's placement right in the heart of Chinatown, the museum is also heavily involved in community related activities. An example of this was a ceremony that I attended in November 2014 honouring the Chinese Canadian war effort and acknowledging the surviving War Veterans. This beginning of this ceremony took place at the Chinese Canadian war memorial located across the street from the museum. As part of the history of rights issues in Canada, war memorials mark the heritage landscape as physical sites to gather and remember and this act of gathering creates a sense of collective memory about this time in Canadian history and the experiences of those that endure it.

*Interesting critique of the monument from 2010 article in the Vancouver Observer: http://www.vancouverobserver.com/politics/commentary/2010/06/04/location-monument-chinese-canadian-veterans-ineffective

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The second part of this ceremony took place over dim sum at a near by restaurant, an event that I was honoured to be invited to join. I was reminded here of what a community the museum has created. Those I interviewed shared stories with me of checking in on vets, helping them with errands, and making sure they are connected to the larger community of Chinese Canadians for events and special occasions. The CCMM, as one of my research participants historian Henry Yu reminded me, first and foremost exists for the community. It is not heavily advertised, or easy to see from the street. It is not drawing in huge visitors or created exhibitions that stretch out of the main focus of the institution. The exhibitions produced, material objects collected, and the oral histories recorded, all come together to create an important record of Chinese Canadian experiences during the Canadian war effort in the early 20th century.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Center in Burnaby, BC is an interesting example in Canadian museological history as it was created directly from compensation received from the Japanese Canadian redress process that took place from the 1970s into the 1980s. In 1988, the redress movement resulted in the government’s acknowledgment and apology for the Internment of Japanese Canadians during the 1940s. The museum and cultural centre were conceived as a place to have exhibitions, hold community events that focus and celebrate Japanese heritage, and exist as an archive of the Internment period. This included actively recording the oral stories of elders in the community, collecting photographs, ephemera, and objects, and serving as a research center for projects and activities related to Japanese Canadian history (Thomson et. al 2002).

I was conscious that Nikkei Centre is part of a heritage network that links the museum and cultural centre with places such as Hastings Park in east Vancouver where Japanese Canadians were first held after being forced from their homes. In this sense, the Nikkei Centre is also connected to the many Internment sites across Canada, such as New Denver, where one of my participants was working at the time of our interview. As I discuss further in my dissertation, this network also serves to link the staff and community partners together to draw on the experience of the network to research and educate about this history in Canada’s past.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

The primary focus of the exhibitions created at the Nikkei Museum is to tell of the history of Japanese Canadians and their communities in Canada. Re-Shaping Memory Owning History: Through the Lens of Japanese Canadian Redress, the inaugural exhibition curated by the Nikkei Centre’s first Director and Curator Grace Eiko Thomson, opened in September 2000 in what was then called the National Nikkei Heritage Centre. The exhibition focused on the experiences of the Internment and of seeking redress using a mix of narratives from survivors, poetry, photographs, newspaper clippings, and government documents (Thomson 2000). It was the first exhibition in Canada to share the Internment experience through the voices of the Japanese Canadian community. When the exhibition closed in 2001, it moved to other locations in Canada before returning to the Nikkei Centre to form part of the exhibition TAIKEN. The museum has since then focused their exhibition content to include exhibitions that continue to tell the story of internment through multiple perspectives. Examples include what happened in the time after the internment, how the experiences of children differed then adults, the quest to rebuild communities despite ongoing forms of discrimination, and the processes of working on redress.

TAIKEN is a permanent exhibition that grew from the inaugural Reshaping Memory exhibition. It is primarily text and photography-based with large replicas of government documents and newspaper articles. Several large black and white photographs are situated along with texts and timelines along the hallways and around the doorways of the second floor of the Nikkei building. Though simple in design TAIKEN tells the story of early Japanese settlement in Canada, the Internment process, and the fight for redress from the 1950's onward. It is an exhibition that tells of the experience of Japanese Canadians in Canada. The upstairs of the Centre has classrooms for teaching, meeting rooms, and offices for staff. In this sense, as children attend Japanese language classes, the story of their ancestors blankets the hallways as a reminder of what occurred in Canada’s past. The exhibition wraps the upstairs of the Center somewhat poetically, in the story of redress.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

This photo is part of the permanent exhibition TAIKEN. This exhibition panel was the only time in all my travels that I saw the phrase human rights incorporated into an exhibition—aside from obvious thematic exhibition material in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. I incorporate reflections on this phrase by my participants in Chapter 5 of my dissertation, as it was curious to me to note how little the phrase was utilized in exhibitions dealing with rights-based issues.

At the onset of this project I had not really factored in the significance of whether this term was being used, however asking my research participants to reflect on this phrase and the use of this phrase in an exhibition resulted in some interesting and varied responses. Most I interviewed felt it seemed too obvious, too political, or too cloaked in the rhetoric of the United Nations. For some, they has not really thought of it, or considered that particular exhibition work might be, in fact, human rights work, though upon reflection most agreed that was in fact what a number of curatorial projects are. It is worth noting that because the term is associated with these international doctrines where what rights are and who gets to decide are some how set aside from those involved in the fight for equal rights, most I interviewed felt it unnecessary or uncomfortable to label work "human rights".

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Unlike the CCMM, the Nikkei Museum is not located in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. There is an area around Powell Street, known to the Japanese community as “Pauera-Gai,” where the original community of Japanese settlers was established in the late 19th century. People I spoke with offered both positive and negative reflections on this location. Given that space is limited in the inner city and parking is increasingly difficult to find, the location of the Nikkei Centre in Burnaby, with ample parking and a large building, means the centre can accommodate community events, exhibition openings, markets, and large crowds for various programming events. However, not being physically present as an institution in the Powell St. area of downtown where the Japanese community once was located means that much of the work to remember and re-establish this physical presence is done by distance. As much of Vancouver's Downtown Eastside undergoes processes of gentrification there is fear that both Chinatown and the former "Japantown" will disappear. As buildings in the area degrade, the question of what gets preserved in the name of cultural heritage and what is slated by the city for demolition are the focus of heated debates in the context of Vancouver’s current real estate market.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

An example of these debates occurred just as my research began in summer 2014 around Oppenheimer Park. The park sits near the centre of the former Japanese Canadian community in this part of the city. It was once the home field of the Japanese Canadian Asahi baseball team and today it is the site of the annual "Powell Street Festival" that has celebrated Japanese Canadian culture and community since it first took place in 1977. The park is also situated in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) community; a community with a high number of low income residence and many people who live on, or close to the streets. For many people, this park is not only a place of connection—it is also a place to sleep. This park became a site of protest when members of the DTES community and Musqueam Band members occupied it to draw attention to the shockingly large number of people who continue to struggle in Vancouver due to the lack of low-income residences and processes of gentrification. This protest and ongoing debates in the city of Vancouver about this neighbourhood and its residences show the multiple layers of occupation and displacement that have occurred here and the struggle that various cultural groups are battling to maintain a presence in this part of this city.

A recent research project The Right to Remain takes up these issues of displacement, gentrification, lack of low-income housing, and the disappearing unique cultural aspects to the Vancouver Eastside. As a collaboratively designed project with community members, artists, and researchers, this project highlights the struggle many residents from this area of the city endure to be try and maintain their lives in this part of the city. I take a closer look at the importance of research projects such as these in Chapter 4 of my dissertaiton and how they find a home in smaller museum institutions where it is possible to make very explicit and critical statements about rights.

Right to Remain Project:

http://www.revitalizingjapantown.ca/r2r/

CBC Article on Protest:

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Nikkei does not have a large collection of objects. This is partly because objects from the period prior to the Internment are scarce. The history of the Japanese Internment in Canada is a history of forced relocation. Along with relocation came dispossession and the loss of material goods. Many families only took a small number of their personal belongings with them thinking that they would soon return home. Sadly, this was not the case and personal items, along with homes, cars, fishing boats and all that made up the livelihood of this community, were taken and sold. My interviews at the Nikkei Centre were held in the back area of the museum. I was struck at some point by the stack of suitcases beside me. Suitcases make up a substantive portion of the material collection at the Nikkei because it was one of the only things that people had. And so, as I sat interviewing members of Nikkei Museum staff, this material presence of movement—of moments of hastily packing what few items could fit, of forced removal— surrounded me. The presence of these material objects emphasized for me the significance of a place like the Nikkei Centre and Museum. It is a place that is a keeper of this history of displacement, but also of the time before and the time after. It is an archive of family and community experiences; experiences that are rooted in being both Japanese and Canadian.

Landscapes of Injustice Project - a research group that is working to relocate items and property lost through disposition:

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Nikkei Place is a place for seniors. The Senior Heath Care and Housing Society offers several services ranging in degree of care for elderly JCC. The Nikkei Seniors residence is directly attached to the building with a small grocery store and restaurant. The presence of this place means that those who live here are close to the centre for events that occur; their presence is an essential part of the community that has grown around the Nikkei Centre. As I take up more extensively in Chapter 4, Nikkei Place is in part how Nikkei works to maintain tight connections within the Japanese Canadian community. Like the Chinese Canadian Military Museum, much of the work comes with maintaining connections with the elderly community, those who went through the internment, and to draw upon their knowledge in project development.

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014

Glenbow is unique in that it is a municipal museum, art gallery, archive, and library set right in the centre of downtown Calgary, located off the heavily pedestrian area of 8th avenue (Fig. 70) and surrounded by shops, pubs, restaurants, and the theatre district. As a result, the Glenbow is situated as part of the arts centre of city. The Glenbow grew from the collection of the founder Eric Harvie who began collecting objects from around the world in the 1950s after a successful career in resource extraction. Harvie's collection was initially focused on Indigenous and Canadian frontier histories, though he expanded his interests to collect objects from around the world. In 1966, he donated his collection to the Province of Alberta. Additionally, Harvie sponsored many other arts and culture institutions in Canada including: the physical building of the Glenbow Museum; the Banff School of Fine Arts; the Luxton Museum; the Calgary Zoo; Heritage Park; and Confederation Square and Arts Complex in Charlottetown, P.E.I. (Harrison 2005; The Glenbow 2016).

Information on Glenbow: http://www.glenbow.org/about/

Image Copyright JCRobinson 2014